Amy Kelley

Amy’s journey to now is solid, and circuitous.

Amy Kelley’s journey as an educator is beautiful and rich, one that circles through career choices and cycles through intentions and detours to enduring contentment. As Amy winds her way through her career for us, we have the feeling that the actual position she holds – humanities teacher, language arts department chair, MTSS coordinator - matters less than her life’s work - her deep understanding of students - who they are, how they develop, grow, learn, and how they present themselves to the world. She never settles, never reaches a final destination. There’s always more to figure out, which is at the heart of what makes her a distinguished educator with a fascinating story.

““I never intended to go into education. I looked at journalism carefully. I planned for a long time to go to law school. I was admitted to law schools. I have a degree in economics. I thought seriously for a time about doing development work in other countries.” ”

Amy describes in detail about her parents both being in education, and what effect that had on her, both encouraging and discouraging her path.

“Both my parents were in education. My dad was a college professor and an administrator, first at St. Mike's and then at a school in Virginia. My mom taught all over the place, the Lund Home…, Edmonds Middle, Rice, summer programs at Burlington High School. She ended up teaching in the prison system, so totally different environments, but they were teachers, before they were anything else. I had teacher parents and that meant every field trip I ever had was educational; they had really strict, high standards for schooling.

And now I appreciate all of that. And I have since subjected my own children to all of that.

At the time I thought, I don't want anything to do with school. Although I love school and I was happy in school. Long story short, I went a different route.”

Amy was in graduate school at Tufts University working on her PhD in English when an opportunity arose.

A friend’s husband was teaching at a small progressive private school in Providence, RI, one of the first schools to join the Coalition of Essential Schools. She’d heard a lot about it. They needed an English teacher. Amy had become restless and ready for something different.

”I visited the school and it was very different. There's a whole school meeting every day and kids checked in and were respected and cared for in a way that was really refreshing.

This small, vibrant little community just felt lovely. And so, I jumped and I took a leave from the graduate program I was in. I planned to go back, but I didn't. I was there for four years and I learned how to be a teacher kind of the sideways and back door way.”

The Assistant Head of School was in and out of Amy’s humanities classroom, often ready to reflect with her on what she'd seen and heard. In retrospect, those coaching conversations were invaluable. Amy learned a great deal, something for which she is now quite grateful.

“I probably never said half the thank you’s I should have said. ”

“The thing about a small school is that it's really easy to drown in kids’ situations, especially in a high school where kids are growing up. They're testing limits, and they're asking questions, and their families are messy. Yet there was this intense satisfaction of seeing these kids grow up and go off to school. To work, go off to the military, go off to college, to have these lives with purpose. And I thought that is where it's at, but I was homesick.

A position in Vermont was her next step. She had had a good education, and sound content knowledge, but lacked the teaching license. She started taking classes in education, and was able to secure a long-term substitute position in the library at Lake Region. She began by working on her teacher licensure, both taking classes and completing peer review, and was successful.

…I've been here for 22 years. So that's the long and short of how I wandered into education.”

Relationships with her students is primary.

“I love my students. They're busy making a hundred thousand different decisions on a given day about who they want to be and what they want to do. What I value most is walking alongside them and hearing them out while they do that. Trying to influence that in some way, that is good stuff. That is, it's also maddening on any given day.

It's gut wrenching and heart stopping and it's beautiful. And it's clearly where I am supposed to be. It just took me a while to figure that out. I am absolutely certain that education is where I want to be. I am not 100 percent sure that I have found the role in education that I like best.

I know I'm committed to doing this work. I'm not sure how to use the skills that I've got most effectively. That's what I've been casting about for, I think, for a long time. I absolutely love teaching. I enjoyed being the department head. I like the position I have now as MTSS coordinator because I can move in 10 minutes from dialing in closely on the situation of one student to looking at our whole program and how it affects [all] students in grades 9 through 12, I like being able to do both kinds of work.

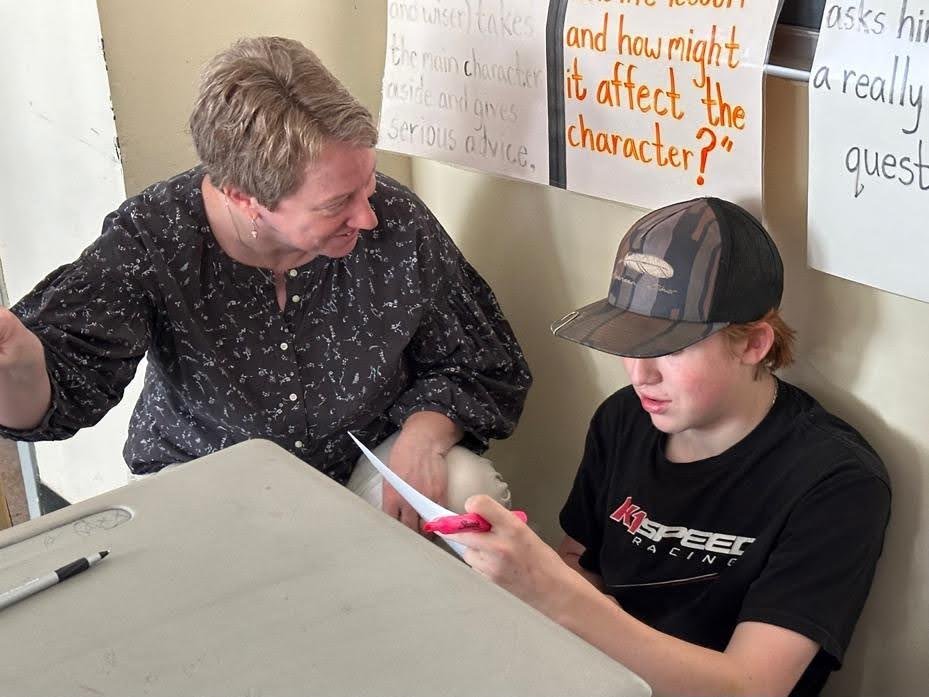

When we first started talking about having the MTSS coordinator position, we knew we'd be talking about assessment, instruction and curriculum. I wanted to hold on to a class. I think if we're asking teachers to try some new strategies, we should be trying them in our interactions with students ourselves.

That's the really satisfying work, and the part of what I really like about the position I have now as MTSS coordinator. I'm still in a classroom. It informs some of the work we're doing school-wide, and also, I'm getting to try out some of the work we're doing with a group of real-life kids that I see every day.”

Seeing the big picture, as well as the detail.

“And I think part of what sold me on this position as the MTSS coordinator is not just that I like data, although I do, and I like playing with numbers and sort of figuring out. Seeing what's missing, doing the big picture work. I like doing the one on one and small group work too, and I like being able to combine both of those in a day.”

When Amy considers the possibility of a future position as an administrator, she would need for that to include some teaching component in the day.

“…and not just teaching out of an office, interactions with small groups of kids, but spending time in a classroom and seeing firsthand where kids are running into trouble, where they're coming in well prepared, where they have gaps.

She might also consider a position at the central office, such as curriculum and instruction, in the future. She certainly has the skillset, experience, and credibility to do that work. But for now, she wants to be closer to students where she can have daily contact and make a difference.

It’s now obvious how Amy found herself in her current post, and how she has created traction rather than burnout, but why rural schools? She could go anywhere – to a bigger school, to a healthier salary.

“For me, rural schools are important because they serve communities and they become part of the community in a way that very few institutions and organizations get to do anymore. They serve wide swaths of the community and not just isolated groups within. And they become places kids actually build community with adults and get to practice living in community and being responsible to each other and caring for each other, learning from each other. That is possible in schools of any size, but I think it’s easier to do that in a smaller rural school where kids grow up together. And, you know, the size of the school can also be a challenge. By the time some of our kids have graduated, they are tired of each other and happy to be heading in different directions.

But I think they've learned a lot from connecting with each other over a long period of time, that sort of longitudinal connection or relationship proves to be really valuable to a lot of our kids. My own students become family. You hear teachers say that, I think that's true in schools of all size, but it's truer in schools that are small, where you get to know kids because your class sizes are smaller. You see kids in the hallways long after they have left the classroom. You see them in the cafeteria. You see them at or on the soccer field and in theater productions and in all the parts of their school experience when you're in a small school.

And so, I think …part of what I like about my position as MTSS coordinator is that I get to use my time differently almost every day. And a lot of that is being where teachers need me to be.

And I've always tried to do that. You know, when there was a theater program that needed somebody to do that work, I can do that work. Trying to be a colleague to the music teacher who's a singleton in our building and supporting her programs. But also sitting with a class if need be so a teacher can do what needs to be done.”

Amy had great role models for that. She appreciated the gift of strong building principals, providing teachers with answers to their questions as quickly as they can. She thinks their teachers are really good and deserve that kind of service.

Lake Region Union High School: a special place!

“You know, in the Lake Region, we've been really lucky. We've had really supportive boards over time. We've had a really strong faculty the entire time I've been here. It's been a really stable faculty. We have really strong leadership. It's been a wonderful place to work.

Every corner of this building works, and kids’ needs are met by lots of different people pulling ahead in different directions. Kids are really lucky to be here. They don't always see it that way, but it’s pretty clear that they really benefit from some time spent at Lake Region. It feels good to be this confident about, this proud of a school.

There are times that I felt really good about the work we've done, creating the senior exhibition process, really good work. I think we learned a lot about what we value most in having those conversations about which transferable skills to hone in on, thinking about how to structure that program. seeing improvements in our curriculum that come from that.

And so, kids go off into the universe knowing how to do some of the most important things. And there’s a satisfaction in knowing that they're prepared with those skills that will allow them to chase after topics that are interesting to them.”

Amy’s own children went to Lake Region High School, and she believes this was essential to both their development, and her ability to see them in a different light.

As part of their proficiency-based graduation system, students at Lake Region, complete projects that give them practice with and demonstrate the transferable skills. Beginning in ninth grade, students work on these projects over time, and as seniors, present what they have learned.

“It's really powerful to see them at the front of the room, really reflecting carefully on how they've grown. More than one … has reduced the room to tears over time. They often are really funny. Watching kids be thoughtful about how their interaction with the school system has helped them to become who they want to be or set them up to head in the path that's important to them is a good reminder to everybody in that room, parents, teachers, kids alike, that education is really important. And in small schools, in a rural community, because some knowledge of that kid may go back even further or may have been developed through classroom time and time on a theater program, on a sports field, time on a trip to Puerto Rico or Mexico, because you've all those layers of interaction, you see those kids’ victories, even the small ones, as the successes that they are because you have a better sense of the struggle that's gone in to that moment of achievement, I think, about graduations in small communities like ours.

It's a community event. The place is packed. There are people at graduation, not because their kids are graduating or their grandkids or their nephews or nieces, but just because somebody in the community is graduating. And there's something really moving about that. There's something really powerful about that.

Students graduated in cars during the pandemic year. My son was a senior, and so off we went in his vehicle along the parade route, not expecting there to be a whole lot of bystanders. It was a lengthy parade route from the fairgrounds of Barton to the high school in Orleans. And there were cars lined up that whole way to support kids taking this big leap in this sort of rotten stretch of time, showing up in a way that I think communities often show up for kids in rural places because those kids feel like everybody's kids. It was one of those moments that reaffirmed that a community school is a valuable place, not just for kids, but for the community in which it's situated.”

Full circle and longevity.

Amy doesn’t regret for a minute changing course. She has no regrets about leaving the PhD program, law school; there’s no looking back. She’s moving forward to what feels right. To bring this full circle, it is easy to draw similarities from her parents’ influence on her to teach and lead, and from her internship in RI to her career at Lake Region.

As Amy’s mother would catch up with her former students on the streets in Burlington, or in chance meetings, these now adults would be eager to tell her mother where they had been and what they'd been up to since they last saw one another. It was really important to them that she knew.

And the coolest thing about running into these students is that my brother and I could never tell from my mother's interactions with them where she had taught them as students – public school, shelter, incarceration.

”She just had this way of making them feel important to her. And I think about what a strong example that was for me. I didn't know that I would ever be in a similar position.

The one thing I would say is that I think the fact that I don't think I'm good at this is probably the reason I have stuck with education as long as I have. I'm determined to be good at this someday. It's important to me to become good at this. So probably if I just keep after it, I'll figure out something worth sharing.”

The listener may beg to differ with Amy’s assessment of being good enough; however, if it keeps her working in the profession with success and a sense of satisfaction, we’ll keep that a secret.